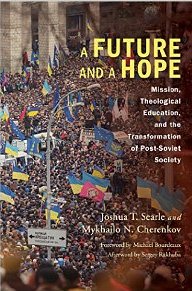

LOI Steering Committee member, Dr. Tim Grass, offers us this review of A Future and a Hope: Mission, Theological Education, and the Transformation of Post-Soviet Society, by Joshua Searle and Mykhailo T. Cherenkov (Published by Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4982-0252-7).

LOI Steering Committee member, Dr. Tim Grass, offers us this review of A Future and a Hope: Mission, Theological Education, and the Transformation of Post-Soviet Society, by Joshua Searle and Mykhailo T. Cherenkov (Published by Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2014. ISBN 978-1-4982-0252-7).

If relationships between Orthodox and Evangelicals are to move forward, especially in regions where they have traditionally been marked by tension and antagonism, it is the younger leaders who are likely to have to do the work. Some of us who have taught as guest lecturers in Eastern Europe have therefore been saddened to see the emphasis laid upon Western patterns of training and theological perspectives, even while we have ourselves been part of the problem! This book, by two young Evangelical theologians with experience teaching in seminaries in Ukraine, explores how the pattern of ministerial formation has to change, raising issues which are relevant in many other parts of post-Communist Europe. It comes with a commendatory foreword from Michael Bourdeaux.

The primary emphasis is on the need to integrate theology, mission, education and ministry, something which inter-confessional dialogues might usefully consider attempting. Perhaps the book’s most penetrating challenge is on the need to differentiate between support for the state authorities and principled engagement with society. In their opinion, churches have often been better at the former than the latter. But a reformed church would participate in a relationship of equals with state and society, maintaining a balance between engagement with the world and rejection of its distorted values. This is contrasted with the threefold commitment to Orthodoxy, autocracy and nationalism which has sometimes been advocated.

Whilst there is (as might be expected) some excoriating criticism of Russia and of the contemporary Russian Orthodox Church, this does not lead the authors to reject Orthodoxy out of hand. They draw on the history of Russian and Ukrainian Evangelicalism in thought-provoking ways, for instance in their comments about the presence of the Orthodox ‘third Rome’ ideology in earlier evangelical leaders such as Prokhanov and Martsinkovsky. This serves to underline their stress on the extent of Orthodox influence on the Evangelical mindset in the region. Accordingly they encourage Evangelicals to seek to relate to Orthodoxy, but by deploying a historical perspective rather than one which is shaped by Orthodoxy’s current political standpoint. Evangelicals and Orthodox, they argue, share a common history, in which each can be seen as supplying what is lacking in the other.

There are aspects of their argument which I might see differently, but my only real problem with the book is that it is written in a dense and jargon-filled style; it reads as though the readership they have in mind is that of fellow academic theologians. We need to be getting the message across as clearly and unambiguously as we can, and to several different audiences: ministers, ecumenists, denominational leaders and theological educators – not forgetting those outside the ecclesial structures whose calling it is to ‘dream dreams’ and ‘see visions’ of what could be, under God. I wish this book – and the vision of its authors – wide influence.

Tim Grass

Senior Research Fellow, Spurgeon’s College, London